The Lie of Knowing: What the Serpent Didn’t Say

- Michael Fierro

- Aug 1, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 3, 2025

We’ve heard the story so many times that we stop asking what it means.

Adam and Eve. A serpent. A tree. A bite.And a line that echoes through every generation since:

“You will be like God, knowing good and evil.”—Genesis 3:5

The serpent’s promise seems almost holy. Who wouldn’t want to be like God? Who wouldn’t want wisdom? Discernment? Moral insight?

But that’s the trick.

Like all effective lies, it’s not entirely false. It’s just incomplete.

What the serpent doesn’t say is how they will come to know good and evil.

And that’s the real tragedy of the Fall.

Adam and Eve didn’t gain insight like judges or philosophers .They gained experience like sinners.

They came to know evil the way a wound knows a knife. And they came to know good by losing it.

The Word “Know” in Scripture

To understand what went wrong in Eden, we need to look more closely at a single word: “know.”

In Genesis 3:5, the serpent promises:

“God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

At first glance, the word know might seem harmless—almost admirable. After all, Scripture praises knowledge. Wisdom is a gift of the Spirit. God even says through the prophet Hosea, “My people perish for lack of knowledge.” (Hos 4:6)

But in Hebrew, the word used here—יָדַע (yadaʿ)—doesn’t mean intellectual awareness alone. It means relational knowing—the kind of knowledge you enter into, not simply observe.

Yadaʿ is the word used when Scripture says,

“Adam knew Eve, and she conceived...” (Gen 4:1)

It’s not about data. It’s about union. Experience. Participation.

We see this elsewhere in Scripture too:

To “know the Lord” is to be in covenant with Him (Jer 31:34).

Israel “did not know” the Lord when it abandoned His ways—not because they lacked information, but because they broke relationship (Judg 2:10).

Even in judgment, God says,

“I will set my face against that man and make him a sign and byword… and you shall know that I am the LORD.” (Ezek 14:8)

To “know,” then, is not a neutral act. It implies closeness, response, accountability.

And when that kind of knowing is applied to good and evil, we have to ask:

What kind of knowledge did Adam and Eve actually gain?

Was it a contemplative grasp of moral categories? Or was it the direct, embodied experience of evil?

What the Serpent Promised

The serpent’s words are deceptively simple:

“You will be like God, knowing good and evil.” (Gen 3:5)

On the surface, it sounds like an appeal to wisdom. And not just any wisdom, but divine wisdom. To “be like God” and to “know good and evil” suggests the possibility of moral clarity, discernment, and spiritual maturity.

And in fact, these aren't bad things.

Scripture often tells us to seek wisdom. Solomon prays for discernment between good and evil and is praised for it (1 Kings 3:9–12). The psalms speak constantly of the righteous man who delights in God’s law and lives by it.

So what’s wrong with what the serpent offers?

The answer lies not only in what he says, but in how he says it, and what he leaves out.

The serpent tells a half-truth—a lie by omission. He offers something that sounds like the goal of the spiritual life, but without the means that God has ordained.

He offers wisdom without obedience. Divinity without grace. Maturity without trust.

This is the heart of temptation: To take what God intends to give, but to grasp it in our own way, on our own terms, and outside of relationship with Him.

Eve looks at the fruit and sees that it is:

“...good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise...” (Gen 3:6)

She doesn’t desire evil. She desires a good thing, but seeks it through a disobedient act.

This is often how sin works. It doesn’t begin by tempting us to pursue what is obviously wicked.It begins by offering something good, but in the wrong way, or at the wrong time, or for the wrong reason.

The desire to “know good and evil” wasn’t inherently evil. But the lie was in the method.

They were promised the knowledge of God, but what they gained was something very different.

What They Actually Gained

The serpent promised they would be “like God, knowing good and evil.”And in a sense, that promise came true.

“Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked…”—Genesis 3:7

Their eyes were opened. They did gain knowledge. But not the kind they expected.

They didn’t become like God in wisdom or holiness. They became like rebels in shame and fear.

They came to know evil not as God knows it—from the outside, in perfect justice and holiness—but from the inside, by participation.

They didn’t discern evil. They did evil. And they didn’t grasp good. They lost it.

Their eyes were opened, yes, but what they saw first was not deeper wisdom.It was their own nakedness. Their own vulnerability. Their own guilt.

The knowledge they gained wasn’t abstract. It was relational rupture. Suddenly, they hid from God, from each other, even from themselves.

This is the tragic irony of the Fall: They reached for wisdom and gained alienation. They wanted to be like God, but they ended up knowing good and evil in the one way God never does, by breaking communion with Him.

God knows evil as a judge. The redeemed know evil as something to resist. But sinners know evil as something done and suffered.

Adam and Eve didn’t ascend to divinity. They descended into exile.

And yet, even in that descent, God’s redemptive plan was already at work. Because their story was never going to end with a broken tree and a fig-leaf cover. There was another tree still to come.

The Pattern of Sin

The story of Adam and Eve is not just about something that happened. It’s about something that keeps happening.

We are always tempted to reach for good things the wrong way.

Sin rarely presents itself as evil outright. More often, it comes dressed as wisdom, freedom, or growth.

It whispers the same message the serpent spoke in Eden:

“You will be like God…”

You’ll finally take control. You’ll finally understand. You’ll finally become what you were meant to be.

But instead of trust, it offers autonomy. Instead of obedience, it offers self-assertion. Instead of receiving, it invites grasping.

This is the pattern we see over and over in Scripture:

At Babel, humanity tries to ascend to heaven on their own terms. The result? Scattering and confusion.

Saul, anointed by God, grasps at the priestly role that wasn’t his. The result? Rejection.

Even Peter rebukes Jesus for speaking of the cross, offering his own plan for glory without suffering. And Jesus calls it what it is: satanic.

In each case, the root sin is not always the desire, but the manner of seeking.

Good things—pursued in disobedience—become distorted things.

That’s why so many modern errors are difficult to challenge. They often begin with something true:

The desire for love

The longing for dignity

The hunger for healing

The call to justice

But when those desires are detached from truth, when they are pursued outside of God’s design, they become dangerous.

This is what the serpent knows. He doesn’t need to convince us to hate God. He just needs to convince us that we’ll find wholeness without Him.

That’s the ancient lie. And we keep falling for it.

Christ as the True Tree of Knowledge

If the first sin was an attempt to grasp divine knowledge through disobedience, then the redemption of that sin had to come through obedience, not grasping, but self-gift.

That’s exactly what we see in Christ.

Where Adam seized, Christ surrendered. Where Eve reached for wisdom, Christ embraced the Cross. Where humanity tried to rise, Christ descended to raise us with Him.

St. Paul puts it plainly:

“Though He was in the form of God,He did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped,but emptied Himself…” (Philippians 2:6–7)

Adam tried to become like God by disobedience. Christ, who was God, became man by obedience.

In doing so, He revealed what it truly means to know good and evil, not by experience of sin, but by resisting it, not by pride, but by love.

Christ knew no sin (2 Cor 5:21), and yet He carried its full weight. He bore evil without participating in it. He judged it not by theory, but by dying under its burden—and rising again.

He is the true Tree of Knowledge. But this tree is the Cross.

And it doesn’t lead to shame, but to salvation. It doesn’t alienate, it reconciles. It doesn’t promise wisdom while hiding death. It offers life and gives it fully.

The irony of the Gospel is that the path Adam and Eve thought they were taking, into divinity, is only truly possible through Christ.

He is the Way. He is the Truth. He is the Life. And only through Him do we come to know God rightly.

Only through Him do we know good without evil, and truth without distortion. Only in Him is the serpent’s twisted promise undone, and the Father’s eternal purpose fulfilled.

Why This Matters

It’s easy to treat the Fall as ancient history. But the deeper danger, the desire to grasp wisdom without God, never really left us.

We still chase knowledge that bypasses obedience. We still seek growth without grace, healing without holiness, experience without limits.

Modern culture tells us that truth is something you discover by exploring everything. Try it all. Feel it all. Decide for yourself.

Experience becomes the ultimate teacher. Personal authenticity becomes the highest virtue. "Live and learn” becomes our excuse for nearly anything.

But Scripture is clear: Not all knowledge is safe. Not all experience is good. And not all self-discovery leads home.

The first sin was not rooted in hatred or malice. It was rooted in the lie that to become more you must break free from the God who made you.

That lie still echoes today.

It echoes in the voices that say the Church is repressive, that commandments are outdated, that holiness is naïve.

It echoes in the subtle temptation to “learn the hard way”, to sin in order to understand, to wander in order to find yourself.

But Christ offers a different path.

Not one of control, but of communion.Not one of grasping, but of receiving. Not one of self-definition, but of transformation.

He doesn’t invite us to experience evil to understand good. He invites us to become good, by abiding in Him.

And that requires trust. Not blind trust. But the trust of a child who knows the One who made them is also the One who knows what’s best.

In Christ, we don’t lose our freedom. We finally know how to use it.

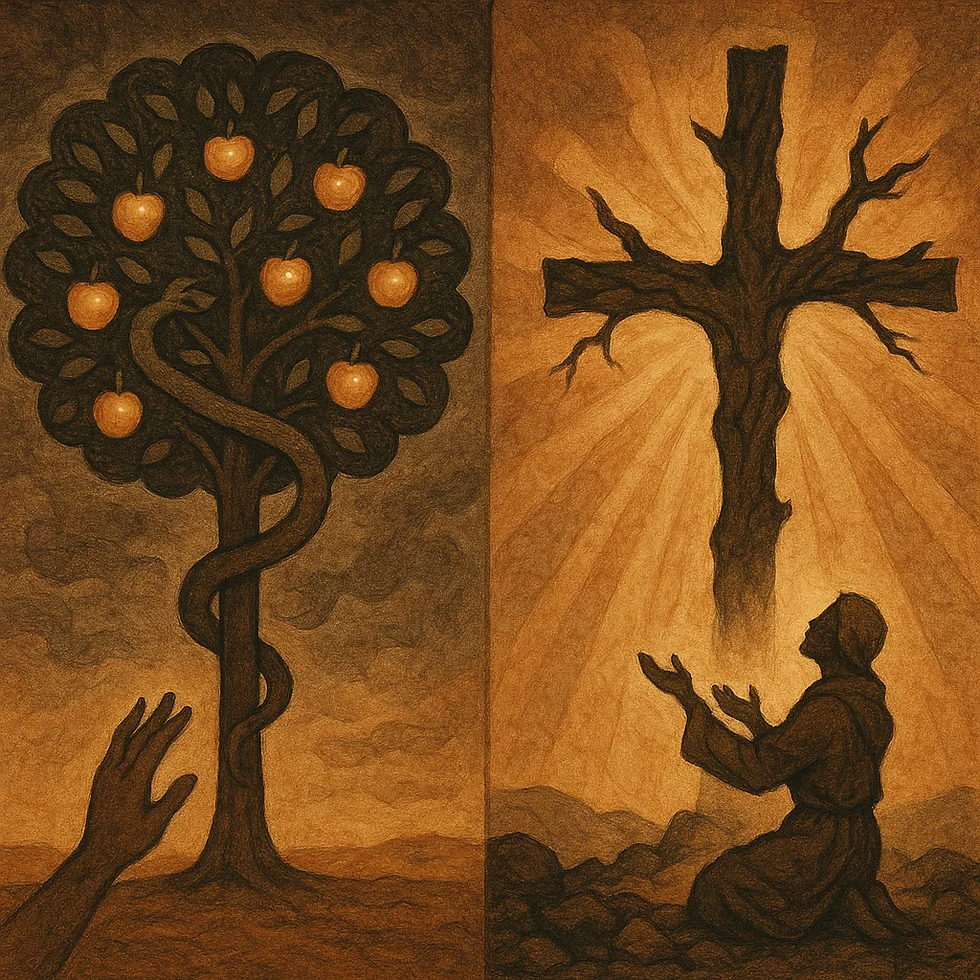

Conclusion: The Two Trees

The story of the Fall begins at a tree. But so does the story of our redemption.

In Eden, the tree was pleasing to the eyes, desirable for wisdom, but forbidden. At Calvary, the tree was hideous, soaked in blood, and it opened the gates of paradise.

Adam and Eve reached out their hands to take. Christ stretched out His hands to give.

One tree promised divinity and delivered death. The other embraced death and delivered divinity.

The first was grasped in pride. The second was climbed in love.

And so the question before us is not just whether we will choose good over evil, but how we will come to know the difference.

The serpent’s path says: “Taste it all. Decide for yourself.” Christ’s path says: “Abide in Me. Let My Word shape your heart.”

The lie of Eden was that knowledge leads to life. But the truth of the Gospel is that life leads to knowledge, and life is found in Christ.

There are still two trees before us. The tree of self-will and the tree of the Cross. One invites you to take. The other invites you to trust.

Only one of them leads home.

Comments